Ultima

Jul 28, 2004 · peterb · 14 minute readGames

[Shelf 1 (of 4)](http://www.tleaves.com/weblog/images/articles/obsolete- shelf.jpg)

Nostalgia, in general, is an emotion that I am suspicious of. We grow by moving forward, and though sometimes that involves looking back introspectively, nostalgia is the opposite of introspection: it is the fetishism of the past. Some part of the past is thought of as good because it wells up nostalgic feelings, rather than because of anything one can qualify objectively. I try to consciously choose introspection instead of nostalgia whenever I can. However – as the regular reader may be able to guess – when it comes to obsolete videogames, I am completely in thrall to the teenager in my head.

I don’t think this is uncommon. If you ask people (or at least American men) who grew up in certain eras what the best video game consoles were, you will get different answers – I’m in the Atari 2600 camp, those about 5 years younger than me will talk about the original Nintendo Entertainment System, those a few years younger than that will talk about the Sega Genesis or the SNES, and so on. Basically, whatever your first console was (or, whatever the first console that your best friend had but your parents wouldn’t get for you was, so later in life you feel compelled to buy them on eBay. Er, not that I’d know), that’s the one that you feel nostalgic for. This works for old home computers, too, and of course computer games.

The most recent wave of nostalgia to overcome me is the “Ultima Classics” package put together by one very obsessive-compulsive fan. It’s floating around the ether, and if you have a Windows PC and are at all interested in classic games I recommend you track it down. I actually already own all of the Ultima games – some in their Apple ][ incarnations – but the sheer comprehensiveness of the collection inspires nothing short of awe. Included are every version of every Ultima game (except Ultima 9) for the PC, Apple ][, Commodore 64, Vic-20 (!), and Amiga platforms, along with emulators to run the non-PC native ports. Also included are various fan-authored remakes and ports (such as Exult and XU4), full documentation for every game, and just to add insult to injury a series of videoclips of Richard Garriott (a.k.a. Lord British) talking about his work.

This, therefore, seems like a good time to talk about the Ultima games and their progress through the years.

_Time and travel made me wise

precious gold, a clue it buys!_

[ ](http

://www.tleaves.com/weblog/images/articles/ultima2.jpg)

](http

://www.tleaves.com/weblog/images/articles/ultima2.jpg)

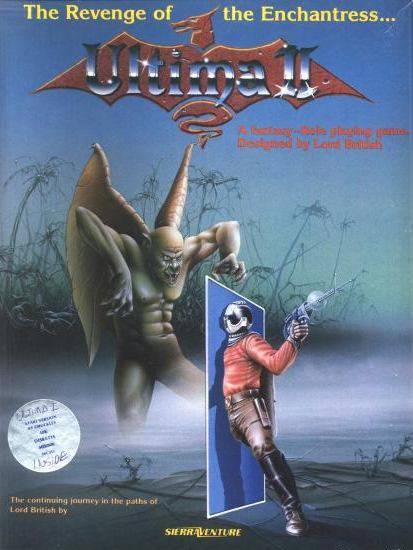

The first Ultima game I played was Ultima II. I remember staring at the fabulous box cover art in a software store – in 1982, when the idea of a store that sold software was itself an innovative and risky idea – and saying to myself, “I must have that”. The packaging was part of the excitement of the game – it came with a wonderful cloth printed map of the Earth. Very spiffy.

The goal of Ultima II was to kill the Enchantress, Minax. I wasn’t too clear on why she had to die, but the game manual said so, and I was a big believer in obeying authority. (Minax, it seems, was the apprentice of the wizard the player allegedly assassinated in the first Ultima game, but I hadn’t played that yet). Sure, it’s standard fantasy garbage, but it was very well packaged standard fantasy garbage. At the age of 13, I found the very idea of a powerful, evil villain being a woman to be very surprising, even transgressive. Ah, innocence.

_Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies

The Queen is the King and the King is a spy_

I liked a lot of things about Ultima II. I liked that it was fast. I liked that it took place on a map of Earth rather than in some amorphous fantasyland. I liked that it had time travel, and that the portals you walked through were called “moongates” – that sounded really cool and science fictiony. I liked the various eras you could travel to: there were frigates in the seas in the middle ages, go back far enough in time and you’re in Pangaea, go ahead far enough and you find yourself in a world after the nuclear holocaust. I liked the little staticky <braaaaaap> sound the game made when you hit a bad guy.

The game centered around combat, which was fast and furious: enemies walked up to you in the wild and you beat on each other until one of you died. Despite this focus, there was a plot of sorts. You could talk to every townsperson; 90% of them had nothing interesting to say (every fighter, for example, would say “Ugh, me tough!” and every cleric would say “Believe!") A small minority of townspeople (often behind locked doors, almost always standing still) would give you bits and pieces of the plot, or clues about where to look next.

One of the best parts of the game, for me, was the space travel. The entire solar system was modeled (to a minimal degree) in the game; you could land on every planet, and every planet had at least a small human outpost, which you could walk around and talk to people at and advance the plot. Realistic? Of course not. Fun? Absolutely: just the idea of saying “Hey! I wonder what kind of colony is on Mercury?” is enough to stir my imagination. Maybe I’m an easy sell, but I found this enchanting as a teenager, and it still makes me smile today.

I finished Ultima II in record time, and was desperate for more. Rumors swirled that there would be a sequel, but I couldn’t wait that long. I found Garriott’s first game, Akalabeth (informally, “Ultima 0”) at an Apple retailer in Westfield, NJ, hanging in a cheesy ziplock bag on a rack, and also picked up the first Ultima game at the same time.

I needn’t have bothered with Akalabeth. While it has collectible cachet today, it’s pretty much intolerably unplayable, and anyway is incorporated wholesale as basically the dungeon parts of Ultima I. I played Ultima I through to completion throughout 7th grade, but it was painful. It looked just like Ultima II -- at least in the “outside” world – but was painfully slow; there was a delay of about a quarter-second each time you took a step. And the cities were primitive compared to the later game. Still, perhaps because I had some lingering guilt over my brutal murder of the Enchantress from the latter game, I pressed on, determined to seek karmic balance by committing the crime for which she sought revenge. Ultima I is littered with odd bits of literary flotsam and jetsam (“Find the Pillar of Ozymandias!” the King commanded me, and when I dutifully reached it – I was still following orders at that point in my life – a few lines from Shelley’s poem were among my reward). The incorporation of literary themes by reference was common in the days before advanced graphics were vivid enough to be representational enough standing by themselves. To this day, one of my most vivid memories from that era is playing a text-based Star Trek game which, for no apparent reason, would occasionally emit page-long quotes from Marcus Aurelius' Meditations. Every so often, driven by nostalgia, I scour the internet, looking for it. I haven’t found it yet. I’ll never find it. If I ever do find it, I will be disappointed.

(One bug in Ultima Classics v1.3, by the way, is the lack of the original Ultima. The organizer included two versions labeled “original” and “enhanced,” but this is a mistake – the “original” version he includes is in fact simply another copy of the “enhanced” assembly language rewrite that Origin did in the mid-80s. The original Ultima, written entirely in glorious Applesoft Basic, can still be found at the Asimov Apple ][ archive, or on rotting 5 1/4” floppy disks of those of us old enough to have bought it and lame enough to have kept it as a souvenir.)

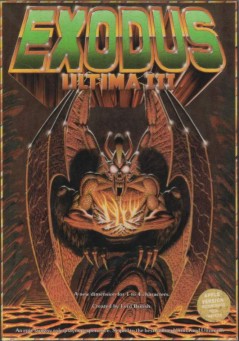

Finally, after months of endless waiting, Exodus: Ultima III was released. It was the last Ultima that I actually played to completion; it was also the last Ultima that was released while I was in Junior High. That’s not a coincidence. The plot – well, the plot is exactly the same as the previous two games, Minax and Mondain had a child, Exodus, who threatens the peace of the world, so could you please go kill him? Thanks!

Exodus had real music, if you shelled out the money for a “Mockingboard,” a sound card for the Apple ][. I begged and pleaded with my dad, trying to somehow convince him that this was essential to me eventually having a lucrative and rewarding career as a software developer (Hey, Dad! It worked!) and he eventually gave in and bought the damn thing. I loved the music.

The biggest change was that instead of being a lone adventurer wandering the wide world, you controlled a party of up to 4. Somehow, this made the game social: every day after school, Albert Bobowski and Paul Castlegrant would come over and we’d play Ultima III until late into the night, confusing the hell out of our parents who didn’t understand what we were doing on the computer for so long.

Another change in Ultima III was the introduction of tactical combat. When you encountered an enemy on the world map, the view changed to a tactical map where your party would be confronting a group of enemies. You could then manuever around the map, shooting arrows, casting magic spells, and whomping on each other. Most people think of this as a great improvement, but my tiny simian brain actually preferred the simpler, faster combat of Ultima II. The tactics don’t really change much throughout the game, so once you figure out the One Correct Way To Win Battles, it’s all just stretching out the game.

Paul, Albert and I eventually did finish Ultima III, learning the horrific secret of Exodus and returned to our normal juvenile deliquent activities. It was two years until the next game, Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar came out. I got it, and played it quite a bit, but by this point school and after-school activities were competing with videogames for attention. I loved the intricate plot of the game, and the focus on developing your character’s virtues. To this day, I can’t tell you what the Christian seven deadly sins are, and I can’t tell you what Buddha’s Eightfold path, is and I can’t tell you what various Jewish mitzvot are, but I know instantly that the eight virtues of the Avatar are Compassion, Honor, Justice, Valor, Honesty, Sacrifice, Spirituality, and Humility. What’s my religion? I’m an Ultimist!

Once you perfect your virtues, however, the rest of the game is basically a dungeon crawl, and combat in Ultima IV was even slower than in Ultima III. I simply told myself that from an ethical standpoint, I had fininshed the game by becoming the Avatar of Virtue, and moved on. Fundamentally, once you’ve slogged through one dungeon, you’ve slogged through them all.

Ultima V came out right as I went to college. I bought it, but didn’t have an machine to play it on (I tried playing it on one of the library’s Apple ][s, but the environment was just all wrong.) I’ve tried playing it a few times since then, but haven’t truly gotten in to it.

Ultima VI I saw while working at one of the computer clusters in Wean Hall. I poked around with it a bit, but I found its mouse-based nature offputting. A year later, I did end up trying the Martian Dreams game based on the same engine, and played it to completion. I’m a sucker for a good alternative universe, and taking a spaceship to Mars with Sigmund Freud, Mark Twain, Nelly Bly, and H.G. Wells was beyond my power to resist. It was a well-written game, and I’d play it again if I could make time.

By the time Ultima VII came out, I was in grad school, and even three years after it came out computers still weren’t really fast enough to actually play it and have it be bearable. It’s only in the past few years, with the success of the open-source Exult project, that playing Ultima VII has become a reasonable option for most of us. It turns out it’s a reasonably OK game. Who knew? Certainly not me: my experience with U7 was so bad that I gave up on the franchise completely.

It was around the time that Ultima III was announced – Reagan was President then – that people started making jokes about how “Ultima 9” and “Wizardry 12” would be coming out in the late 90’s. It was kind of a backhanded slap to the very idea of sequels in computer games: every year, games come out which are totally new, which are totally innovative. As if we’ll be playing the same old tired genre games twenty years from now! As if the fickle computer game player could possibly have that much desire for continuity.

And, of course, now there is an Ultima 9, and every year another Madden football game comes out, and every year people buy the new one, and innovation, when it comes to actually making money on games, is more of a curse word than a byword.

And here’s where nostalgia is our enemy: the temptation to say that it is the older Ultima games that are better, because they are somehow “purer,” that later games in the series were panned by critics and fans because they weren’t “true” to the spirit of the game. This is a lie. The purity of the earlier games is nothing more than a memory of the purity of youth, when you could use a game with a terrible user interface and inconsistent pacing and not notice. The Ultima games are remarkable for their consistency, both in vision, character, and mechanics, even until the end. The things that were good in the very first ones – epic scope, quirky characters, a unique sense of place – are good in the very last ones. The things that were not very good in the very first ones – terrible user interface, langourously paced plot, the drudgery of combat – are not very good in the very last ones. Only the implementation details have changed.

There is, I think, something special about the original Ultima games when compared to their contemporaries. They had a unique narrative voice that sprung from their being the product, essentially, of one man. That’s not to say his narrative voice was the best of all possible ones; merely that it was unique, and that the player can feel this. Compare it to, for example, two games that have nearly the exact same graphical quality, scope, and game mechanics of Ultima: Chris Crim’s The Wrath of Denethenor and Xyphus. They’re both eminently playable, but they’re missing some ineffable element.

What that element is, I can’t say. I know it when I see it. But I know that it is more likely to come from the mind and heart of one person, such as Brad Wardell, then from any design committee in the heart of NCSoft or Blizzard.

Pining for the days when one man could program an epic adventure and bemoaning the fact that all ‘big’ games today are designed by committee: that’s nostalgia. Thinking about how we can commit enough resources and large enough teams to create a modern video game while still maintaining the design integrity and vision that a single designer brings: that’s introspection.

Additional Resources

-

Here is the info file for the Ultima Classics collection, detailing exactly what it contains. Marvel in its obsessive-compulsiveness.

-

If you don’t want the whole shebang that is the Ultima Classics collection, you can pick them up piecemeal. The Exult project is your best bet for experiencing Ultima VII on modern PC hardware. For Ultima IV, you’ll want to download XU4 (Kudos to Electronic Arts for making the source code to Ultima IV public domain!) Some of the other games in the series are available freely, or nearly so, on the net. Let google be your guide.

-

If you’re desperate for a boxed set, and don’t want to sully yourself with bittorrent, you can buy a perfectly legal version of The Ultima Collection from Amazon. Then you should go download Ultima Classics anyway just to get all of the emulators and PC utilities correctly packaged to make playing them easy.

-

Ultima-alikes The Wrath of Denethenor and Xyphus. Both are available from the Asimov Apple ][ archive.

-

Contest! For extra bonus geek points (and without looking it up on the web) tell me what Minax says if, instead of attacking her, you talk to her. Correct answer wins absolutely nothing except the admiration of millions, or at least tens.