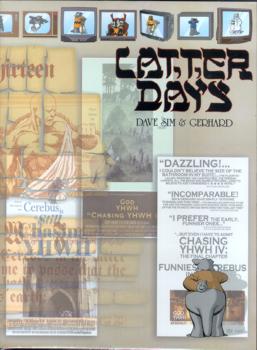

Latter Days

For those unfamiliar with it, Cerebus is mixed-media pictures and text, black and white ink on paper, originally released as 20 page bound pamphlets, periodically bound into folios referred to as “phonebooks.” That’s how you’d describe it in a museum, anyway. A more concise description would be “Cerebus is a graphic novel.” A less pretentious description would be “Cerebus is a comic book.” The most recent “phone book”, covering the penultimate chapters of Dave Sim’s epic work, is entitled Latter Days.

This by itself guarantees that practically no one will read it. The American literary establishment is composed of people who are, by and large, afraid of visual art; unless the art is safely caged within a gallery or a museum, its presence is threatening, intimidating, confusing. Every ten years or so The New Yorker or some similar arm of the prep-school cultural politburo will publish a brief item by some bewildered trust fund baby who just discovered that maybe Art Spiegelman’s Maus isn’t really for kids. They talk about the article at a gallery opening. “Well, of course, I’ve known about Spiegelman for years, darling. I met his wife, Françoise, in the Hamptons last summer.” Even more galling to me are the articles about Japanese manga and how adults in Japan read them, completely ignoring the vibrant work, such as Cerebus, that you can find right here.

Then they ignore the medium for another ten years.

So comic books occupy a singular place in American culture. Everyone — without exception — has read them at some point or another. The “funny pages” are probably the most fought over section of newspapers in busy households, and the political cartoon is still alive as an acceptable art form for adults to enjoy. Beyond that, the medium has languished in the children’s ghetto mostly because of distribution issues: since most of the money in the medium is to be made from kids and teenagers, the major distributors focus their marketing and distribution efforts there, which retards the growth of the adult graphic novel market. It’s a bit of a vicious circle, although the fact that most mass market bookstores at least have a graphic novel section is a sign of some small improvement.

The unique position of comic books in our culture is a recurring theme in Cerebus, which isn’t surprising given Sim’s role as one of the most prominent self-published writers. It sometimes has negative aspects. Comic book characters and, often, their authors make appearances throughout the text as extended in-jokes. So, for example, if you don’t know anything about Todd McFarlane’s Spawn character, or about McFarlane’s reputation as a ruthless capitalist who can turn anything, anything at all, into a profitable merchandising opportunity, some of the early parts of Latter Days will simply go over your head. More often, though, it works. Sim’s world — like our own — is a world of semi-illiterate people. In that world, small books with mixed pictures and text are simply called “reads.”

Sim writes “reads.” So, he would argue, did F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oscar Wilde, and Ernest Hemingway, all of whom appeear in earlier chapters of Cerebus. And in comparing himself to, appreciating, and in some cases brutally critiquing these writers (he dismisses Hemingway, in particular, as a mere “typist.”) Sim is reminding us of a simple, unavoidable truth: it’s not the number of words per page that makes a great writer great. It’s what those words are, and how they are used. The division of texts into “comic book” and “novel” is not, primarily, a literary distinction. It is a marketing distinction, and an indication of the seriousness the reader chooses to assign to the text.

Latter Days is worthy of being treated seriously. As in all his later works, Sim chooses an author and deconstructs his work through the eyes of his characters. The author in question this time around is: God. Well, if you believe that God wrote the Bible, that is, since that’s the text Cerebus is analyzing (having been Pope once, Cerebus is more qualified than most to be able to opine on scripture). I don’t want to reveal too much about the plot of Latter Days, but you can infer a bit from its guest appearances, which include The Three Stooges, Woody Allen, and the films of Bergman and Fellini. One of the “in-jokes” that works better than most is Cerebus’s obsession with a comic book called The Rabbi (“Cerebus knew it was great literature, because it had lots of pople being killed in different ways.”) which features a superhero with an unending (and hilarious) list of Secret Rabbi Powers (“Rabbi Hernioplasty Touch!” “Rabbi Dextrorotary Breath!” “Rabbi Fully Detachable Foreskin!”).

Latter Days is thoroughly a modernist work, although the author would be repelled by that label. Nonetheless, it is: every panel of the work is aware of and obsessed with its form. Cerebus is maddening to read in serialized form, because Sim makes no concessions to the format. There is no guarantee that in any given 20 page span of the novel anything will “happen”; perhaps he will cinematically “pan” over an area for several pages, establishing the locale. Perhaps there will be a few empty black boxes, which are surrounded by paragraphs of dense prose. Frames are arranged in a variety of ways. Figures break out of their frame. The reader may need to rotate the book in order to read for several pages. Another example: in Latter Days, towards the end, we are shown a long, seemingly endless pastiche of panels which have no narrative connection to the text at all. Intentionally. The author is poking fun at the reader: “Don’t you wish I’d stop all this boring writing and thinking and just show you more pretty pictures?” he seems to be saying. Like much other modernist art, Cerebus makes you work. It is no exaggeration to say that Sim has expanded the idiom of mixed-text-and-pictures the way Joyce expanded the idiom of the modern novel. His work is that revolutionary.

Lastly, no discussion of Sim and his work is complete without at least some reference to his misogynism, perhaps the biggest piece of baggage he took away from his divorce. Sim hates when people label him misogynist, or theorize about why he went over the edge the way he did, but given that he has written entire books discussing how various writers’ personal lives influenced their writing I feel quite guilt-free labeling him. His incomprehension of and disgust for women is, indeed, odious, and quite on display here.

Which goes to show you: someone can write well and still be a raving lunatic. Sometimes, although thankfully not always, the two are related.

So with respect to the bee he has in his bonnet about women being the anticreative force in the universe, a force which is opposed to the creative male principle, yet seeks a “merged permanence” in which it will absorb and destroy the male essence, we can say confidently: Sim is crazy. He’s not eccentric, he’s not odd, he’s crazy. This is a man who speaks his own language with the confidence of the someone who thinks deeply about everything except his own prejudices: of course “God” and “YHWH” are different — but real! — entites. Of course YHWH is the feminine principle, and is thus sneaky and untrustworthy. Of course God created Freud to cause World War II to cause the sacrifice of millions of Jews to pay for the blood debt they incurred.

Back in 1990, I interviewed Sim for a radio show; I just found the digital audio tape of the interview not too long ago. In the interview, my co-host Steve Peters, asked him “So, how did the divorce from your wife and business partner Dani influence your work?” At the time, I was mortified — I practically made throat cutting motions at Steve when he started asking the question, not wanting to embarrass the artist. Now, given the uglier parts of the work (which to be fair, hadn’t been published at that point) I wish I’d had the desire to pursue that question, rather than avoiding it.

Arguing with Sim is, pretty much, like arguing with Ralph Nader — both are convinced not only of the rightness of their cause (who isn’t?) but that such rightness is self evident, and that therefore anyone who claims to not see it is either lying, evil, or brain damaged. I guess I’d fall under “evil” — I understand the arguments that Sim is making very precisely, because I’ve seen so many variations of them from delusionals of different stripes. Only the persecuting “them” differs between stories. Sim is a fruitcake. A nutbar. He’s crazy.

With that said, I can also say: so what? Latter Days, taken in isolation, is the best thing Sim has ever written. Taken as a single chapter of the Cerebus project, it is unparalleled. Put in context, it is thought provoking and more evidence of his continued development as a serious writer. I read an author’s work when I find his style and subject compelling and visionary, even if I disagree with him. I disagree with Sim on a lot of things. But Cerebus is both compelling and visionary, and I am richer for having read it.

Additional Resources

- You can buy Latter Days at your local comic book store, or from Amazon.com

- Andrew Rilstone wrote a superb in-depth analysis of the final issue of Cerebus, and shares some thoughts about Sim’s descent into paranoia. Warning: contains spoilers.

- An interview with Dave Sim from 1992, before he was quite so far gone. Keep your eyes open for alert Tea Leaves reader Jon Ferro offering wisdom on board games.

I’m half convinced that people who write articles on comics for top-flight papers and magazines are partly doing it to prove how “cool” they are.

Cerebus is brilliant, in spite of mysoginistic tendencies.