The second most tiresome thing about the “there’s too much violence in these newfangled videogames” discussion is that violence has always been a part of games.

The argument is made, usually poorly, that today’s violence is “worse” because graphics today are so much more vivid than they were in the past. This is twaddle. More accessible, perhaps, but not necessarily worse.

One need only to look to Thomas Pynchon’s V for an example of how the written word can depict more vividly than image. Chapter 4, “In Which Esther Gets a Nose Job” still makes me feel faint if I try to read the whole thing through at once, in a way that the goriest hospital video does not. I can only handle it a paragraph at a time. Here’s one of the easier passages, before the going gets really rocky:

Schoenmaker first made two incisions, one on either side through the internal lining of the nose, near the septum at the lower border of the side cartilage. He then pushed a pair of long-handled, curved and pointed scissors through the nostril, up past the cartilage to the nasal bone. The scissors had been designed to cut both on opening and closing. Quickly, like a barber finishing up a high-tipping head, he separated the bone from the membrane and skin over it. “Undermining, we call this,” he explained. He repeated the scissors work through the other nostril. “You see you have two nasal bones, they’re separated by your septum. At the bottom they’re each attached to a piece of lateral cartilage. I’m undermining you all the way from this attachment where the nasal bones join the forehead.”

By the time Schoenmaker gets out the saw, I’m usually ready for a stiff drink. The idea that better rendering of pictures inherently means more powerful images is false. Alfred Hitchcock made an entire career building suspense and emotion based as much on what he didn’t show as on what made it onscreen. If we are to worry about violence in games, it must not be in the mechanics of how it is depicted, but in the emotions it exploits.

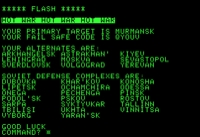

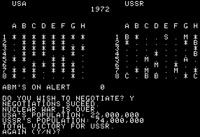

In the early ’80s, Avalon-Hill released a few simple but challenging games, mostly written in BASIC. One was a version of Sid Sackson’s “Acquire”, another was a reconstruction of the Battle of Midway. Two of the ones I liked playing the most were B1 Bomber and Nukewar. I liked them because the goals were clear, the mechanics were simple, and the stakes were high. HOT WAR HOT WAR HOT WAR flashed the screen, and as a patriotic American I understood that it was time to fly to Leningrad, drop a single nuclear bomb, and kill everyone there, because, y’know. That was the job. There’s a war on, you know. Nukewar presented you with the further strategic decision of when, or whether, to start a war. In the screenshot to the right, you can see the results of a game where, as the US, I just sat tight and didn’t start a war, and the Russians beat me to the punch. The lesson is clear: if you want to survive, start a nuclear war. And people want to complain because there are games now that let you knock over a liquor store?

I don’t have an awful lot of sympathy for all the crocodile tears about the violence in games like Grand Theft Auto. Yes: I find it tasteless, I find it demeaning, and worst of all it’s not a very good game. But the quality and scale of the violence therein is not, it seems to me, necessarily any worse than the cold war fantasies of the Clancy generation, who believed (or in some cases still believe) that politics might — regrettably — require the murder of half the people in the world.

I don’t believe that Nukewar and its ilk did any lasting damage to me. I don’t believe that Grand Theft Auto will do any lasting damage to the people who play it. In the final analysis, games are instruments of fantasy. Fantasy, being what it is, often transgresses across boundaries that we do not cross in real life. Attempts to suppress, to channel such imaginings are just another form of fantasy — a fantasy that life is simple, and that we can always recognize evil when we see it. If you want to worry about violence, worry about the violence that is being done on our behalf. Institutional violence, where one person decides that the killing should start, but someone else has to go and do the actual dirty work, is to me the most frightening of all.

And it’s a lot harder to stop a war than to boycott a videogame.