I’m a huge fan of text adventures — the name “interactive fiction”, it seems to me, is way too general, since it could cover any number of similar-but-different media — but they are possibly the most unapproachable genre in the world of computer games. There’s a lot of really interesting work being done with the medium, but it’s pretty much impossible to get anyone who does not already accept the strictures of the form to try them more than once. You can always get someone to try them once. Inevitably, within less than a minute, the new player will try to examine some item that is just part of the “scenery,” or guess the wrong word, and they decide that this is stupid and they don’t need to further subject themselves to the medium.

In one sense, that’s their loss. In metaphorical sense, though, the author of the work just lost a reader because it wasn’t obvious how to turn the pages of the book. Anyone who has ever watched a new player play a text adventure knows exactly what I’m talking about.

>> Grab plate I don't know how to grab. >> Lift plate I don't know how to lift. >> get plate I see no plate here. >> get platter I see no platter here >> get dish Which dish do you mean, the green plate, the blue plate, or the red plate? >> red I don't know how to red.

Presumably, some authors choose the text adventure medium specifically because they like its constraints, and want those pages to be hard to turn. For those authors, the above scenario really isn’t their problem. Others, however, may simply be trying to tell a story, and don’t care about the idiosyncrasies of (say) the Inform parser. For these people, a different system might be appropriate.

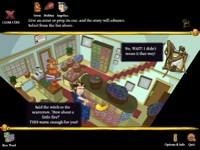

The Witch’s Yarn is, essentially, a “choose your own adventure” book, in the form of a computerized stage play. It is available for both Windows and Mac. Rather than controlling “a character,” the game is presented as a series of scenes, with you as the ‘director’; you queue up characters, items, and events, and then watch the drama unfold. Characters appear and disappear from the stage, speak in text baloons, and otherwise expound on the plot (which I won’t spoil here, but centers around a witch who is trying to interact with the “mortal world” by openin a yarn store.) The wordsmithing is better than you see in most adventure games — I’m including text IF here — but let’s be frank, this is a videogame, not a Henry James novel. The main characters are believable; the supporting cast is very caricature.

There have been other tools that let people develop “choose your own adventure” style games, but the system used for The Witch’s Yarn seems particularly polished, at least from the user’s point of view. Helpful prompts explain how to let the story progress (without dictating a choice). The game is always implicitly saved, so just quitting at any time will always allow you to pick up where you left otf. If you make a mistake and steer the story to an endpoint, the engine allows you to undo the previous choice, or roll back to the beginning of a chapter. The graphics are simple; it looks like cues can trigger simple animations. It’s unclear to me how much scripting the engine allows. At least in The Witch’s Yarn the effect is that of being shown a play performed by Colorforms stickers.

I’m being a little unfair when I describe the game as simply a choose-your-own-adventure book. It’s a little more complicated than that. Rather, the cues you introduce have an effect on the game state; the same cues introduced in a different order can yield different results. So in the second chapter, for example, the main character’s emotional state is bouncing around based on what cues are introduced. Some cues (for example, an aggravating visitor) make her angry. Some make her depressed. Some make her happier. Send in too many “angry” cues in a row, and the story comes to an end. So at least in this chapter, I started thinking of the protagonist not as an actor, but as my little pet finite state automata, and I found myself trying to draw a mental state diagram of all possible transitions.

This cueing system, actually, feels to me very much like what Emily Short did in her artwork Galatea. The player conversed with a character in the game, based on topics the player introduced, the game would take a different course. In that work — which was text based — you basically had to guess-the-trigger. In The Witch’s Yarn, the cues are all presented to you on a silver platter. Other than that, the underlying concept is the same.

The engine that underlies The Witch’s Yarn is called CineProse. The press release from the publisher, Mousechief, has an interesting paragraph that cuts to the heart of the issue:

We believe that current adventure games do not address the constraints of the casual game market. In our user testing, the majority of a sample population was unable to perform basic control over the main character. That´s why we re-invented the genre specifically for this market. Thus, the CineProse style of adventure game was born. Subsequent testing of computer novices showed that 100% of ages 8 to 78 were able to pick up and play The Witch´s Yarn.

There are things one can quibble with, here. It’s arrogant to talk about “re-inventing” the genre when multiple other publishers have “re-invented” the same product, using the same mechanism, albeit not as slickly. And the people who are producing adventure games for the people who already play adventure games are not going to stop what they’re doing and start licensing CineProse: the increased usability it provides is at the cost of eliminating whole classes of user interaction that experienced players of the genre have come to know and desire. But let’s zoom up to the 50,000 foot level and acknowledge: they’re right. The casual game player finds the interface of the typical adventure game bewildering.

The question, then, is how close to the bone can you strip an interface and still be left with something that is fairly characterized as an “adventure game.” That’s a bigger question, and not one i have an answer for.

The full version of The Witch’s Yarn is $20; I didn’t buy it. My calculus went something like this: “Hey, this is a really neat story, and I’d kind of like to know how it turns out. It seems like an interesting play. But it’s not that much better than some of the IFComp games that came out this year. Those are free. Also, $20 would get me a ticket to a community theater performance of some other play that I haven’t seen. I don’t think I want to pay $20 to see how this turns out; maybe if there was more game here I would, because then there would be more of an intellectual challenge. I think this one is a no-go for me.”

So it’s a conundrum. I estimate I would have spent about $10 to see how the story ended. Any more than that, and you start asking yourself questions like “Why don’t I buy a book, instead, which will be longer, probably better written, and can be read away from my computer?” Despite the fact that I wasn’t willing to shell out the lucre, I think that Mousechief has correctly identified a need and has built what seems like a polished product to serve it. The real question to me is: what will happen with CineProse? There’s a few ways it could go. It could remain as Mousechief’s internal engine for their adventure games, it could be licensed to other publishers for use in their games as well, or it could be given away for free to all comers.

I’ve spoken briefly with the developer, Keith Nemitz, and he does indicate that he intends to license the engine, and that there would be no fee for noncommercial projects. This could be a very viable business model. I’ve talked mostly about text adventures as being the alternative here, but graphic adventures have their place as well, and as Ron Gilbert has described in detail, the economics of producing them are gruelling. If the CineProse bundle of Python scripts, SDL libraries, and application software is basically marketed as “produce your adventure game at a third of the cost of what your competitors are doing,” then Keith may do very well indeed.

Giving away the tools for free to noncommercial projects seems like a smart decision to me, particularly if Mousechief can figure out how to monetize it. Off the top of my head, I’d imagine “give the dev tools away for free, but require that the ‘player’ be purchased by the users to view the entire works” might be workable. I’m really not going to pay $20 to read one potentially bad short story. I might pay $40 to be able to read many, if I know for a fact there are some good ones in the mix.

I feel bad saying that The Witch’s Yarn isn’t my cup of tea, because it’s an attempt to look an entire genre in the eye and say “What you’re doing doesn’t work for most users. We’re going to try something completely different.” I respect that. So despite the fact that I didn’t buy it, I still think you should visit their web site and download the Windows or Mac versions, and try it for yourself. And let me know what you think.

Additional Resources

- If you want to kick it old-school, you could check out the results of this year’s Interactive Fiction Competition, and play the top games.

- That being said, the IFComp did manage to completely diss the best text adventure game of the year, as well as the best graphical adventure.

- You could browse the Interactive Fiction archive.

- Read more about Emily Short’s Galatea.

- Want to write your own text adventures? You could start with the manual for the Inform system.

- Want to write your own 2d graphical adventure? Read Ron Gilbert’s article first.

- People have been predicting the death of adventure games for a long, long time.

Thank you Peter for a very tight review. I fully respect your decision not to buy TWY. I had to make a difficult choice about puzzles in the game. During our user playtesting, we found that our chosen audience, women’s segment of the downloadable market, preferred the ‘choose your adventure’ style more than the classic ‘beat your head against the puzzle’ if you fail to ‘get it’. These users are not only frustrated with user interfaces, all but the simplest puzzles confound them and quickly dissuade them against purchasing.

So, in the first two chapters, the demo part, there are no puzzles. However, chapter 3 begins to introduce puzzles, all sorts. They’re mostly simple ones, except for the ‘killer death puzzle from hell in 4D’ lurking in the ice cream shop. The idea was to offer a variety, of which players need only to solve three to proceed past all of them. And you get, in Chapter 2, a pass to solve any one of the puzzles. From there the game presents progressively harder puzzles, hoping to coax new adventure gamers into discovering another kind of fun with adventure games.

I will say this about the CineProse scripting language. The original goal was to make a script look as much like an honest to gods screenplay as possible. We didn’t succeed well enough, but it’s a very friendly language for this kind of game.

Shall I attach my explanation of why your dissing

of text adventures is (partially) unfair here, or

wait for an IF-specific story?

Please, be my guest.

Since Zarf hasn’t said anything yet (I do hope he will, or that you’ll do a bit about IF later), here’s at least one reason that what you said was kind of unfair. Here’s a bog stupid inform source file:

Constant Story “Test”;

Constant Headline “^Because red, green, and blue are good enough.^”;

Include “Parser”;

Include “VerbLib”;

Object TestRoom “Test Room”

with description

“A pretty boring room.”,

has light;

Object -> red_plate “red plate”

with name ‘red’ ‘plate’ ‘small’ ‘translucent’,

description “A small red plate, slightly translucent.”;

Object -> blue_plate “blue plate”

with name ‘blue’ ‘plate’ ‘medium’ ‘rectangular’,

description “A medium-sized rectangular blue plate.”;

Object -> green_plate “green plate”

with name ‘green’ ‘plate’ ‘large’ ‘heavy’ ‘thick’,

description “A very heavy green plate, the largest and thickest

plate you’ve ever seen.”;

[ Initialise;

location = TestRoom;

];

Include “Grammar”;

and a short transcript, based on what you said:

Test

Because red, green, and blue are good enough.

Release 1 / Serial number 041230 / Inform v6.30 Library 6/11 S

Test Room

A pretty boring room.

You can see a red plate, a blue plate and a green plate here.

>grab plate

That’s not a verb I recognise.

>lift plate

That’s not a verb I recognise.

>get plate

Which do you mean, the red plate, the blue plate or the green plate?

>red

Taken.

>x blue plate

A medium-sized rectangular blue plate.

>get rectangular plate

Taken.

>get plate

(the green plate)

Taken.

So you see here that the standard inform libraries (pretty commonly used nowadays) at least do the “Which plate do you mean…” thing correctly. As far as unknown verbs (grab, lift), and really stupid name choices (dish), that’s kind of a “Of course, if a moron is writing the game it will be bad” problem. On the one hand, I didn’t add “grab” and “lift” to my example, because “take” and “get” are really the common verbs for that action. On the other, I didn’t do something stupid like give “red plate” the names ‘red’ and ‘dish’ and not ‘plate’.

So there’s a certain amount of “The author has to be smart enough to do smart things” going on here. For example, I write my plate game (above), and see that you (a playtester) try these commands:

grab dish (not a verb I recognize)

lift dish (not a verb I recognize)

get dish (you can’t see any such thing)

get plates (you can’t see any such thing)

This tells me a couple of things: First, I need to expand my repertoire of verbs (not really that likely, get is pretty common, but for other actions it’s quite likely.) Second, I haven’t covered all of the bases on the plates for names. Someone might call them dishes (not at all unlikeley), and more importantly, I haven’t included plural names. So I change the source like so:

1) I add after the Include “Grammar”; bit:

Verb ‘grab’ ‘lift’ = ‘take’;

(Note that this is almost identical to an example given in the Inform Designer’s Manual, on how to extend the set of verbs.)

This just says that “grab” and “lift” are synonyms for “take”. It’s possible that I’ve already added a verb “lift” for something else, like “lift curtain” to raise the curtain on a stage or something. If so, I may have to do a bit more work here to differentiate the possibilities. But still, it’s my job as the author to do that.

So now, grab and lift plate will work.

2) I change my plate definitions like so:

with name ‘red’ ‘plate’ ‘small’ ‘translucent’ ‘dish’ ‘plates//p’ ‘dishes//p’,

I’ve added the noun “dish” that can be used to refer to these, and also added “plates” and “dishes”, with //p at the end to indicate that they’re plurals. So now:

>grab dish

Which do you mean, the red plate, the blue plate or the green plate?

And this works for all of “grab”, “lift”, “take”, and “get”. And more importantly:

>grab dishes

red plate: Taken.

blue plate: Taken.

green plate: Taken.

and more interestingly:

>grab all the dishes except the red plate

blue plate: Taken.

green plate: Taken.

So now the system knows that dishes is a plural (and plates is a plural), it all works better.

And of course, I carefully check over the rest of the objects in my game to make sure that they all have plurals defined when they should. And I send it through another round of playtesting to look for more problems.

So it’s not a constraint of the *system* of text adventures that these things don’t work, it’s a question of whether the author has done all of his or her homework. It’s true that certain things are expected of a player of adventure games–that she’ll know that “get” or “take” is the common verb for taking, for example. (And Zarf has recently released a great new game, “The Dreamhold”, which is an attempt at a tutorial text adventure: it watches what the player does and tries to give advice on what things might work, and includes an excellent help system describing the basics of text adventures.) But it’s also true that most games will add new verbs, and that certain puzzles have to be careful about which verbs work and which don’t. This “guess the verb” problem is one that writers of IF have to watch out for.

In any case, the point is that a text adventure is a program like any other: there are certain expectations of the user interface (which, since text adventures tend to be small and short, it’s hard to teach a new user about in *every* game), but there are also usability concerns. A game that doesn’t handle these issues well is a *bad game*, but that doesn’t mean that all such games are bad. Just like it’s possible for a graphical user interface to break the user’s expectations, but that doesn’t means that all graphical games are bad.

John.